Truth, goodness, beauty & steampunk

The steampunk aesthetic, at its best, grounds technology within the human condition, imaginatively illustrating how technology can serve truth, goodness and beauty, rather than trampling them.

I have seen steampunk criticized as an empty aesthetic. This critique has teeth against cyberpunk (with which I have a love/hate relationship), but in my view misses the mark against steampunk.

Steampunk, at its best, has an enduring appeal for at least three reasons. These are all related to a practical kind of humanism—not a negative placing of humanity into the center of the moral universe (where God goes), but rather a positive placing of human nature at the center of our technological experience:

Firstly, steampunk satisfies our intuition that meaningful things are acquired by doing meaningful work. When I say “meaningful” I am speaking of our own intuitions about work, based on our bodies and the work we do with them. Steampunk gadgets extend the power of our own bodies and tools in ways that are visible and concrete. We can feel them at a physical level, because we can see (or imagine we see) the actual mechanisms that are working together to produce the outcome we expect—and understand them as extensions or concentrations or refinements of the same work we would do with our own bodies and tools.

No other technology can replicate this with such intuitive force; older technologies are too rudimentary to impress us as much, and new ones are too sophisticated to easily connect to our own bodies. The internal combustion engine, for instance, is marvelous—but even if you understand how it works well enough to form these intuitive connections, its workings are not visible; everything is happening out of sight inside an inscrutable engine block.

Not only this, but steam is elemental and primal in a way no other technologies are. It combines earth (fuel) and air (oxygen) with fire and water to produce an effect in the world through its mechanically satisfying components. In this sense, steampunk taps into a magical view of creation, where I’m using magic to refer to something true and symbolic rather than the occult.

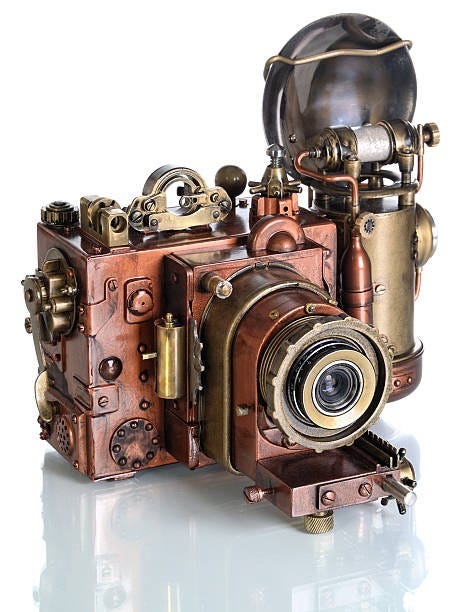

Secondly, steampunk satisfies our intuition that meaningful work is good—and visibly good. Function is connected to beauty. How a thing looks should be related directly to the work it does, and good meaningful work will manifest in a good-looking “worker.” The most primal example of this is again our own bodies. Women are attracted to muscles that do the work they can’t. Men are attracted to the curves that signify fertility. Steampunk follows both the masculine and feminine aspects of this aesthetic logic: it not only has visible mechanisms that satisfy our intuitions about work, but these are crafted to be beautiful as well as utilitarian. In contrast to the brutalist axiology of our age, steampunk does not reduce the form of things down to their barest necessities. One of its most distinctive features is its “frills.” Like human beings, which cannot be reduced down to mere utility, steampunk treats technology as more than the sum of its parts, embellishing and ornamenting it as a thing to be used and enjoyed by people, rather than a means to produce an end as efficiently as possible. It thus captures the value of both utility and style, design and art, exemplifying the masculine glory of strength and the feminine glory of beauty. (This is also, of course, exemplified in the leather-Victorian fashion of steampunk, drawing on a time when what you wore meant more than, “this was cheap and convenient.”)

Most technology tries to do this to some degree, but the demands of industrialization have effectively relegated beauty to an afterthought—and even reduced the bounds of how we conceive it in the first place. This is one of my beefs with cyberpunk. No one a hundred years ago would have thought circuit-boards and concrete were beautiful provided they were mostly concealed in grunge and only highlighted with intense patches of high-saturation color. A world that is stylistically striking and visually arresting is not the same as a world that flows from and builds up the human experience. In cyberpunk, human value is typically an absurdity. It is a disintegrated aesthetic where truth, goodness and beauty exist on the fringe, or accidentally. The world is forced upon humans, rather than the world being fashioned according to the human experience of truth, goodness and beauty. In steampunk, it is the reverse—these things are an integrating principle of the aesthetic. This is perhaps ironic given how much of the Victorian era and industrial revolution that steampunk draws on was ugly and dehumanizing. But it seems to me that steampunk is an effort to redeem and glorify that era, drawing out and extending its best humanist features.

Thirdly, in relation to this, steampunk exemplifies the height of human craftsmanship, rather than mere technological fabrication. Steampunk gadgets are concretely human, rather than the abstract achievements of a milling machine. Indeed, they are gadgets, with everything that connotes. This is not to say that no fabrication is implied, of course, but rather that the finished products look hand-made. There are rivets and seams, and perhaps more importantly, the materials used are generally those we can work by hand. There is a tangible connection between the natural world, the human world, and the steampunk world. Its technology exists within those worlds, rather than being extended out of them. This is perhaps most obvious with its use of lights, which are typically soft orange or yellow, and visually connected to the fire from which all natural light comes in our own experience. But it is also evident in the use of brass, which has more natural glory than iron or steel, being more like gold, which in turn is solidified light. Its softer color and reflective qualities produce an entirely different effect to more advanced metals—an effect maybe captured well in the word “cozy,” which connects it to human comfort rather than mechanical utility. Wood, also, is an oft-used material. Again, natural and familiar—and, being organic, possessed of an inherent beauty that more space-age materials cannot mimic, and which can be further developed through human craftmanship.

This third element of humanism is especially easy to see when we compare steampunk versions of science fiction technology with their originals:

Perhaps the thing that most exemplifies the steampunk aesthetic is the airship. It takes all the best features of trains and paddle-steamers and joins them to the advances of commercial flight, without the dehumanizing elements that came with it. It combines all of the features that I’ve talked about into a single impressive machine that places man at the center, balancing the end to be achieved (efficient transportation) with the human need for community, beauty, pace, place etc. But that might be another essay.

Btw, I am not an expert on steampunk by any means, and I’m not endorsing every way that it is imagined. A lot of it can be ugly and grunge and overly-industrial. But I like the general vibe—and when I ask myself why, I discover that I like it because it is not an empty aesthetic. It is, rather, one grounded in the human experience, and which therefore has lasting appeal to humans.

This holographic article not only highlights the tactile qualities and beauties of steampunk and its connection to biblical humanism, but when one reflects on it at a different angle this becomes an apologetic against the “artificial traits” of AI. Brilliant writeup, Bnonn! 🔥✨