Death and sacrifice before the fall

The pattern of giving something up to a higher thing is found in everything from seeds to offerings.

I want to develop another angle on the symbolism of sacrifices that I wrote about last week.

I want to show how truly foundational this pattern is, and how it should profoundly influence our thinking as Christians. But I don’t think it really does influence our thinking very much — or at least, we have successfully sliced and diced it into a more manageable chunk that will fit into a single pigeon-hole. And while I am very fond of pigeons, especially the fancy Australian ones with the copper bits on their wings, I don’t think that a pigeon-hole is the proper place for something so foundational and so pervasive.

Sacrifice is a pattern that gets into everything. I think every Christian probably recognizes that sacrifice is at the heart of the gospel, so that should give us some hint about its importance. But it is not just a gospel thing. Or maybe a better way to say this would be, the gospel is not something different to how God works everywhere else. The cross of Christ is not like a skyhook that God miraculously hangs from nothing, unattached to the rest of creation, as an utterly unique intervention to save us from the effects of sin. The cross is the peak of the mountain, that builds upon the entire pattern of God’s work in creation — the highest point of a way of life so fundamental to who God is…and who we are as his image…and what creation is, as the physical expression of spiritual realities…that it goes all the way down even to such mundane facts as how plants grow.

Except a grain of wheat fall into the earth and die, it abideth by itself alone; but if it die, it beareth much fruit. (Jn 12:24)

This is a good place to start because there are two things about this verse that are really undeniable:

The first thing is that it is about the cross. And not just Jesus’ cross, but our own. Jesus’ hour is at hand; he is soon to be crucified. In this context, he tells us something important that we can learn from how wheat grows: that if we love our lives, we will lose them, and that if we hate our lives, we will gain them eternally (John 12:23–27). The connection between this and his own cross is not spelled out here, but it is spelled out in a similar passage in Luke:

If any man would come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross daily, and follow me. For whosoever would save his life shall lose it; but whosoever shall lose his life for my sake, the same shall save it. (Lk 9:23–24)

So, when Jesus talks about the grain of wheat going into the ground, the first thing we can absolutely say is that it is about the sacrifice of the cross.

But the second thing we can also say with complete confidence, is that it is about the natural design of wheat (and indeed, most plants and trees). In my last post, I mentioned that sacrifice tends to get put in the pigeon-hole of atonement. That is, at least, the main reason for sacrifice in our minds. Sacrifice is something necessary because of sin.

But if there is one thing that should be clear, it is that wheat had to fall to the ground and die in order to bear fruit…before the fall.

And God said, Let the earth sprout sprouts, plants yielding seed, and fruit-trees bearing fruit after their kind, wherein is the seed, upon the earth: and it was so. And the earth brought forth sprouts, plants yielding seed after their kind, and trees bearing fruit, wherein is the seed, after their kind: and God saw that it was good. And there was evening and there was morning, day three. (Gen 1:11–13)

And then to Adam he says,

Behold, I have given you all plants yielding seed, which are upon the face of all the earth, and all trees, in which is the fruit of a tree yielding seed; to you they shall be for food: and to every living-thing of the earth, and to every flier of the heavens, and to all that crawl upon the earth, wherein there is life, every green plant food: and it was so. (Gen 1:29–30)

Do you notice how strangely the plants are described in these passages? Plants yielding seed, fruit-trees bearing fruit after their kind wherein is the seed. Why the strange emphasis on seed? One reason is that seed is a very important concept in scripture. But for our purposes right now, what we can say for sure is that plants and trees definitively had seeds before the fall. That was a feature that scripture especially calls attention to. Seeds weren’t things that God invented after man sinned. They are part of the creational design. Which means that from the beginning, from even before sin entered the world, the seed had to go into the ground and die.

That’s how they were always designed to work.

I don’t want to labor the point; but sometimes with such obvious things, we don’t notice how important and meaningful they are.

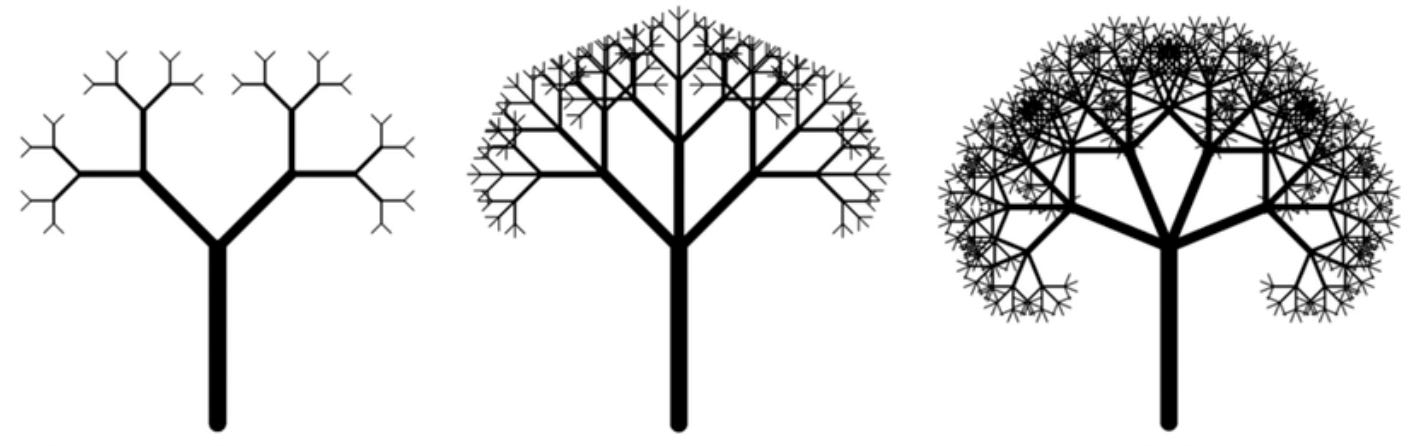

In the same way, consider something else: man is put in a garden full of plants and trees, which he is supposed to guard and serve in order to gain the wisdom he needs to exercise the kingly rule he was made for. The garden is a training ground, so to speak. And the very first instruction he is given is to be fruitful; that is, to bear fruit, as the trees do. We can infer from this that the trees of the garden were supposed to teach Adam about himself, and about key patterns of creation. For instance, trees visibly teach the fractal nature of bodies.

So when Adam is told that he must bear fruit and multiply, God expects him to look at the trees and understand what that means. Adam should expect, for instance, that he himself has seed that must be planted somewhere in order for the fruit to appear.

The second instruction he is given is to eat fruit. By obeying this command, he will soon learn that, if a tree is to multiply itself, its seed must go into the ground and die. Only then will it bring forth new life.

It sounds a bit incorrect to us, to speak of a seed dying, because we have been trained to think biologically. God does not speak biologically, but symbolically, and symbolism is about the appearance of things, the form of things. When a seed goes into the ground, it appears to die. It is swallowed up by the earth. It gives itself up to the earth, and goes into darkness and is not seen again. That is what must happen for a plant to multiply itself.

Adam will soon discover this. But he will also discover that in order for he himself to remain alive — to sustain and grow his own body — the fruit bearing seed must go into him and die. Just as the seed gives itself up to the ground, the adamah, and is swallowed by the adamah, and becomes part of the adamah to produce a new plant…so the fruit gives itself up to Adam, is swallowed by Adam, becomes part of Adam, in order to sustain Adam. It literally becomes part of his substance. And then, I hope you will excuse me, but Adam has to eliminate the part of the fruit that could not be added to himself, and it comes out looking very much like dirt, and goes into the dirt, and somehow makes the dirt more fruitful as well.

If you think these are just incidental facts of creation that Adam was not supposed to reflect on and gain wisdom from about his own nature — and the nature of the rulership and dominion and loving service that God had called him to — then I have another article for you here:

So what is the connection between these creational patterns and sacrifice?

Surely one of the truths that Adam would have discovered in creation was the necessity of death to bring forth life.

I don’t, of course, mean death in the way that we tend to think of that term in light of the fall. I mean death as a kind of disintegration. Adam should have been the integration point of the cosmos: by eating the world, everything was being integrated into him. This is the role recapitulated by the second Adam, into which the cosmos really is being “summed up” (Eph 1:10). But not everything will be integrated into Christ — some will be cast into the outer darkness. They will be “outside;” meaning they’re not contained within the integrating principle.

This doctrine, that Christ is the integrating principle, the arche of creation, is foundational to Christianity, and to reforming it correctly today; it is not a principle well-liked by many would-be reformers, as I discuss, for instance, in this sermon:

Death is dis-integration. Because we no longer understand death properly (perhaps in part due to some oversteering in the world of YEC), it can be helpful to use a different word to describe what it really is. We think of death in biological terms. That’s natural, since scripture certainly does speak of it largely in those terms — after all, human death is the major feature of the world since the fall. And it’s also natural because we live in a world that has made science the measure of meaning, so we naturally look for the meaning of death in science. Thus we imagine the essence of death to be the cessation of physical function.

But that is not what death is as a pattern. It is how the pattern plays out for wicked sinners. And that is because death, as a pattern, is dis-integration. God tells Adam, in the day you eat of the tree of knowledge, dying you will die. What does he mean? Did Adam drop dead when he ate? No. But Adam was cut off from God. And so he stopped being integrated into God, who of course is the source of life (John 1:4). And so eventually — because the physical images the spiritual — this had physical consequences. And so after another 930 years, Adam’s body stopped working.

It took 930 years for Adam to die after he died. 930 years for the workings of his body to dis-integrate after he was dis-integrated from God.

To be dis-integrated from God is the ultimate, terrible death that all men fear. This is, ultimately, the second and final death — which, if you pay close attention, is not biological cessation, but rather unending biological life in torment.

But it is not the only death. Sin-death is an addition to creation. Death was a creational pattern before sin perverted it.

Adam was meant to learn about death through everything in the garden. He would have planted seeds in the ground, and they would have disintegrated to produce new life. He would have pruned trees, and their branches would have been disintegrated from them, in order to grow more abundantly. He would have learned to plow, cutting open the earth, disintegrating the face of the ground in order to make it more fruitful. He would have eaten, disintegrating fruit within his body in order to build it up and sustain it. He would have reflected on the creation of his own wife, who was made out of his own disintegration, both in terms of his mind as he disintegrated into sleep, and in terms of his body, as his own side was torn open to create Eve.

The connection between death/disintegration and sacrifice becomes very clear if we simply ask:

What is sacrifice?

Theologically, we’ve been taught to think of it in terms of atonement or substitution, but in terms of plain everyday English, we all know that to sacrifice something is to give it up. I dare say if you asked anyone what it means to sacrifice something, they would say to give it up.

That phrase, give up, isn’t accidental. We don’t give down. We don’t give sideways. We give up.

The give part makes sense. “Give” really is just a simpler way of saying disintegrate: we take something that is ours, and we make it not-ours. Something that is integrated into us somehow — whether it is property, or a desire we have, or a relationship with someone, or whatever; we take that thing and we break it out of ourselves and we push it away, so it is no longer part of us.

But we do it in a direction.

Why up?

Because the cosmos is hierarchical, and there are things above us — the highest of which is God. There is a great chain of being built into creation. Scientists talk about the food chain, but the food chain is just a scientific way to describe one slice of the symbolic, creational chain: the cosmic mountain. Just as the fruit gives itself up for Adam, because Adam is greater than the fruit, so Adam is required to give up of himself for things that are greater than him. This is the essence of sacrifice. Not substitution or atonement, but a giving of your substance for something greater. Giving of your substance up to some higher thing. A disintegration upward.

But why? It isn’t an arbitrary giving up. We don’t sacrifice just because the thing above us deserves it. The fruit doesn’t give itself for Adam because Adam deserves to eat it. Even Adam does not disintegrate a tenth of his substance to God because God deserves it. God does deserve it — but if you think about it, God also can’t actually use it. He doesn’t need anything, least of all food.

So what is the purpose of the sacrifice? Adam taught his sons to bring offerings to God. Why?

We automatically reach for atonement to answer the question, but while atonement and sacrifice are indeed connected, that, again, is only because of sin. Atonement is a perverse pattern in sacrifice; a pattern that only had to be introduced because of the fall. Man is in danger of disintegrating from God himself, into eternal death — and so some sort of stopgap is required to symbolically show that God is willing to prevent that. So the man gives up an animal instead, and that animal’s life is completely disintegrated; its blood, which is its soul, is poured out at the base of the altar. But that sacrifice only comes with Moses. There is no sin-offering as such before the book of Leviticus. It is added to teach Israel specifically about the need for Christ. But before that, the pattern of sacrifice is still everywhere in Genesis. Cain and Abel bring offerings to God. They are not sin offerings. They are tributes. That is the Hebrew word: a tribute or gift. It is a particular kind of sacrifice later in Leviticus; often (vexingly) translated the meal-offering. It isn’t offered for sin, and Genesis does not say that it is to cover sin. Sin certainly did need to be covered, but these sacrifices don’t seem to be about that. In the same way, Noah offers sacrifices after coming out of the ark. But again, it’s not a sin offering. It is an “ascension.” Another of the Levitical sacrifices, and again, not for sin. Then Abram gives a tithe to God through Melchizedek. Tithes are also introduced into the Levitical system. The word tithe is literally tenth in Hebrew, and you were to give a tenth of everything to God. But again, not for sin.

So what is it for?

Let me answer a question with another question that brings the pattern down to a more mundane level.

Why do you give up what you earn for your family? Or take it back a step. Why do you give up your time and your energy and your attention and your wisdom for your employer? Well, because you get money back — but also, if you’re lucky, because you get to be part of something greater: a body that is achieving something worthwhile in the world. I give up my time and wisdom to you in writing, because I believe that what I build by doing so is of greater value than my own individual desires. Watching movies or playing computer games is more fun, but it is not more fulfilling, because giving up my time and attention to a computer game has no lasting value. Giving it up to the body of Christ is another matter.

Indeed, giving ourselves up to things like computer games (or social media) is a very dark thing, once you begin thinking in sacrificial or sacramental patterns — as I cover in more detail here:

Of course, we don’t always give up our time and labor for such important things. We often do it simply for money. But is that because money matters in itself? No — we give up the money too! We give it up for something that does matter: our family, our household, our church, our friends, our lives.

All of this sacrifice, this disintegration, is for the purpose of integration. We break ourselves apart to be reformed as part of a greater whole. We give up ourselves as individuals to become members of a larger body. We lose something of ourselves by doing so, because we have to accept the meaning imposed by that body. A foot doesn’t get to be a head, even if it wants to be a head; it has to give up its desire for the sake of the body. But a foot attached to a body is a lot better off than a foot not attached to a body, isn’t it? In the same way, we each give up of ourselves, to integrate ourselves into larger bodies that are greater than we are — but nothing we give up is greater than what we get back, because by definition the body is greater than its parts.

When we are integrated into a body, we become greater than we were, because we are part of a whole that is greater than we are.

But we do have to give up something to do it.

This is why sacrifice is a pattern in scripture from the very beginning of Genesis, long before the law of Moses, long before sin offerings, long before the cross. Sacrifice is built into the nature of reality as a matter of necessity, a matter of definition. You cannot have a hierarchy, you cannot have this fractal pattern of bodies, without sacrifice. Any time you have one whole thing that can become part of a greater whole thing, you necessarily have sacrifice. And the rest of creation echoes it. God does not tell Eve, for instance, that he will create pain in begetting sons. He tells her he will multiply the pain.

Eve was already going to experience pain bringing forth children; it was inevitable; it was creational. Sin increased and intensified the pain.

Adam was already going to get tired working. He was made to work. Sin increased and intensified the toil of his labor.

And in the same way, Adam and Eve would always have brought sacrifices to God. Had they never sinned, and instead served God as he commanded, they would always have brought the fruit of their labors to him every seventh day, to give them up to him, and receive them back to eat them with him — because they would always have needed to symbolically, liturgically remember, reiterate, and renew their integration into him as the highest and the greatest thing. They would always have presented their bodies as living sacrifices, holy and acceptable to God, because that would always have been their spiritual service (Rom 12:1). They would always have bowed down before God, prostrating — or as most Bibles will (vexingly) translate it, worshiping — in order to physically express their recognition and submission to the reality that God is higher than they are.

They would always have sought to integrate themselves into God — and God would always have graciously accepted their offerings, bringing them into communion with himself, just as he continued to graciously accept the offerings given in faith by Abel, and by Noah, and by Abram, and later by Jacob and Moses and of course ultimately by Christ.

This was fascinating! Thank you sir. Would you also contend that since plant life does not have the "breath of life" like animals and Mankind, that it's better to refer to plant life as "decaying" and not "dying"? I agreed with the article, just wanting to probe deeper.